When you live far away from where you grew up and marry someone from another culture, carried by the fires of passion, do you think of your parents? Well, you should, especially if you marry an Indian person because then you really marry a family and not only a man or a woman. In the beginning, you may try to protect yourself from the interference of the in-laws in your marriage and private life, without thinking much about how they feel. And then (often) come the children. The parents, busy juggling with their respective cultures to raise their little ones, must also make sure to leave room for the grandparents. How do they find their place in the equation? They are confronted with education methods which can differ greatly and they sometimes have to manage a long distance relationship. While doing my best to make sure my son would develop bonds with both sides of his family, I never thought of asking them how they felt about the situation. Until now! After writing and illustrating Bandati, a book for children of the third culture, I have asked the grandparents how they lived this situation of bi-culturality! An interesting moment of reflections and exchanges.

Part 1 – The Indian grandmother

In India, the daughter-in-law is supposed to live with her in-laws and, in the large Indian family, the baby does not belong to anyone or rather he/she belongs everyone, especially to the grandmother. She is very involved in the life of the infant, feeding him (once breastfeeding is over), bathing him, massaging him, watching over him. On the other hand, there is no real investment in the psychomotor development of toddlers, which is left to the environment; so the bonding does not involve games or activities between adults and children.

My mother-in-law, even though she lives alone, seems to prefers staying in her native Kerala where she has a social circle. Carefully choosing the season – she does not like the cold of northern India –, she visits us once or twice a year for a fortnight. With her grandson, she tried to follow some Hindu rituals at first, but after seeing my face when she covered my three-week-old son with gold jewelry, she didn’t insist. Over the years, she has realized that the best way to bond with her grandson was to “do things” with him. At almost 70 years old, she took up cricket and drawing, and these efforts, at least, made my boy laugh really hard!

Just before sharing her words, let me say that I quite had to gather some courage to ask her how she lived having a foreign daughter-in-law and a French-Indian grandson, especially since direct and transparent exchanges are not common in India. My approach surprised her a little bit – self-reflection and reflection in India are not culturally encouraged – but it was an opportunity to talk about our relationship, and it felt really good!

“April 13th 2014 was a wonderful day for me… I had been delighted to hear that my son was ready for marriage, meaning a daughter in law was coming to our home... Besides that, another happy news: I was going to be a grand-ma soon. That was a dream for us.

When I heard that my would-be daughter in-law was a foreigner, I didn't feel bad… Although I did worry about how my family, especially my strict and traditional father, would react. I also thought communication may be little bit problem, even though I can speak English, not so fluently but can manage. Now I realized I am lucky to have a daughter like mine...

In the case of my grand-son we had a little problem because our togetherness was very rare. So at the age of his 3-4 years, he was not much attached with me. It gave a little pain for me but now he is very much ok, started communicating everything with me as well as my daughter, his paternal aunt. Feeling very happy... The only problem is he can't eat spicy food like sambar which I’m used to making when we are together...”

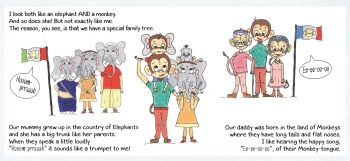

Find more about relationships between grand-parents and multi-cultural children in the book Bandati.